Current Exhibit

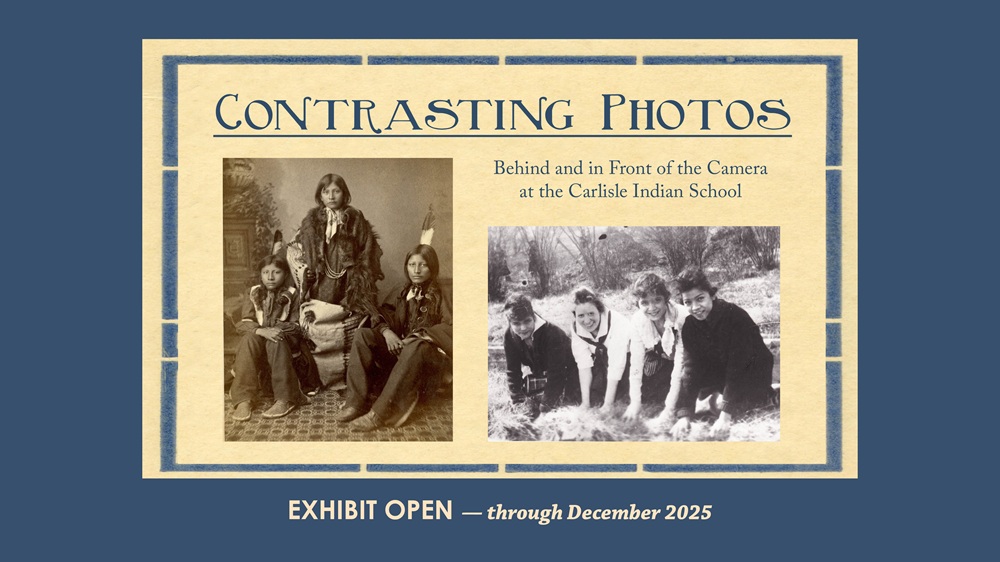

Now til the April 11, 2025 – December 13, 2025:

Contrasting Photos: Behind and in Front of the Camera at the Carlisle Indian School

Cabinet of Curiosities Part II:

The term cabinet originally described a room rather than a piece of furniture. Modern terminology would categorize objects as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings), and antiquities.

Past Exhibits now Online

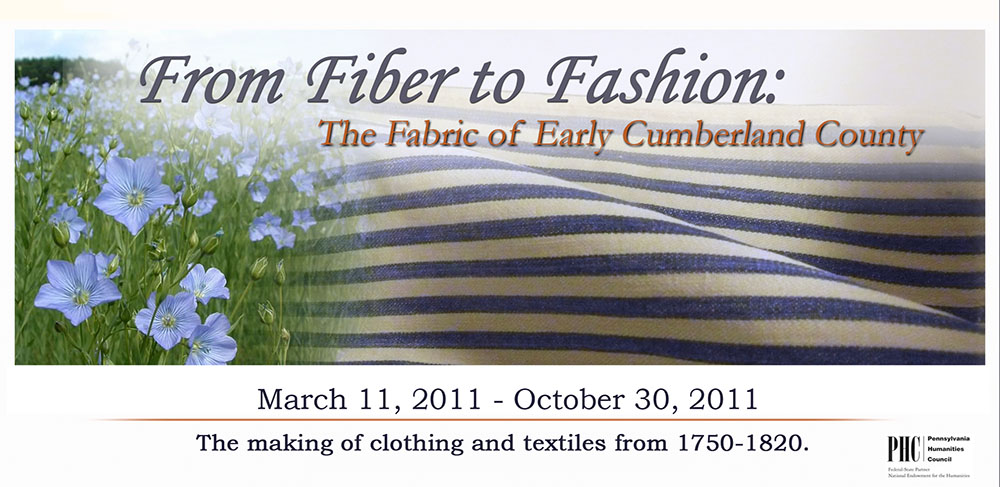

From Fiber to Fashion: The Fabric of Early Cumberland County

What were 18th century Pennsylvania residents wearing and where did they get their clothes? Thanks to a grant from Pennsylvania Humanities Council, in 2011 Cumberland County Historical Society offered the seven-month exhibit “From Fiber to Fashion.” Telling the stories of a local spinner, weaver, tailor, and merchant, this exhibit illustrated interactions with fellow county residents from 1750 – 1820 as well as with merchants from Pennsylvania and Europe. Based on the popular book “Cloth and Costume 1750 to 1800” by Tandy and Charles Hersh, the exhibit featured textiles referenced in this publication, as well as artifacts from the CCHS collection, other museums, and private collectors. Although not originally photographed for an online exhibit, we hope you will enjoy the following photos and labels from this two-gallery exhibit.

Fiber Exhibit

Introduction

From Fiber to Fashion: The Fabric of Early Cumberland County

What were 18th century Pennsylvania residents wearing and where did they get their clothes? Thanks to a grant from Pennsylvania Humanities Council, in 2011 Cumberland County Historical Society offered the seven-month exhibit “From Fiber to Fashion.” Telling the stories of a local spinner, weaver, tailor, and merchant, this exhibit illustrated interactions with fellow county residents from 1750 – 1820 as well as with merchants from Pennsylvania and Europe. Based on the popular book “Cloth and Costume 1750 to 1800” by Tandy and Charles Hersh, the exhibit featured textiles referenced in this publication, as well as artifacts from the CCHS collection, other museums, and private collectors. Although not originally photographed for an online exhibit, we hope you will enjoy the following photos and labels from this two-gallery exhibit.

Making Clothing & Textiles in Cumberland County, 1750-1820

Spanning thirty-five townships and three towns, in 1750 Cumberland County originally stretched to the western edge of Pennsylvania. From its colonial roots to its days as part of the new United States, Cumberland County was on the frontier of a changing landscape. English, Scots-Irish, German, African, and Native Americans lived here. From 1750 to 1825, the county grew from the wild frontier to a land of large farms and businesses. As the county seat, Carlisle was one of the largest towns in Pennsylvania and home to farmers, enslaved persons, tavern keepers, lawyers, doctors, and many others.

The men and women of Cumberland County needed clothing and textiles to furnish their homes. From the county’s beginning, many small storekeepers imported a wide variety of goods from Philadelphia. Fashion demanded that materials offered in large cities and in Europe were also available on the frontier. While fabric was a major import to the American colonies, utilitarian clothing and goods could be supplied by local manufacture.

In this exhibit, based on the book Cloth and Costume 1750 to 1800 by Tandy & Charles Hersh, we invite you to explore the stories of people who lived in Cumberland County and how they fit into this network bound by fibers and fashion.

Cloth and Costume 1750 – 1800 Information in this exhibit is drawn from this book. Many artifacts in this exhibit are also illustrations in the text.

Tablecloth Hand spun unbleached tow linen. This tablecloth was used on the cover of the book Cloth and Costume. The pattern was created by the weaver using huckaback (open weave) and twill (diagonal line) patterns. Collection of Charles and Tandy Hersh.

From Fiber to Fashion – The Spinner

From Fiber to Fashion – The Spinner

Left of “Anna”:

Reel

After spinning, yarn is wound on a reel. A standard of 40 turns of the reel makes 100 yards of yarn, called a cut.

Gift of Laura Zeigler

Thread

Anna Zeigler would have set three pounds of this thread aside for a bed sheet.

Gift of Dr. Charles B. Fager

Making Fiber for Spinning

Raw Materials

Flax

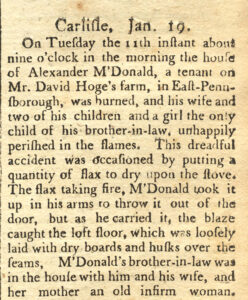

Making flax into cloth is a very labor-intensive process, but it produces a strong, quick-drying durable fabric with a natural sheen. It was common for Cumberland County farmers to grow a quarter to a half acre of flax for each person in the household, every year. Flax was mainly made for home consumption, but it could be traded or sold. Flaxseed was a major export to Ireland, a major producer of linen cloth.

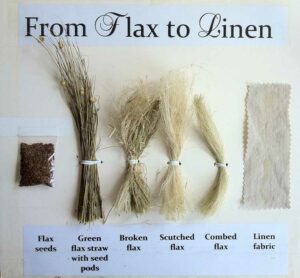

Fields of flax were harvested by pulling the plant out by the roots and drying it. Then, bundles of flax were placed in a field or underwater and allowed to rot in order to loosen the useful fibers. It was then dried again. Then the dried material was beaten using the flax break and scraped with the scutching knife to remove any tough parts or sticky residue. The remaining fibers were pulled through hatchels to refine and align the hair-like strands. The product was twisted into a small strick, which could then be spun into yarn. By the time a strick is produced, over 85% of the original plant has been removed.

Hemp or Flax Break c.1800

Dried stems were placed between the upper and lower wooden slats, then the slats were slammed together to begin breaking up and removing the unusable parts of these fibrous plants. Finishing work would be done with a scutching knife.

Gift of Alexander K. Rice

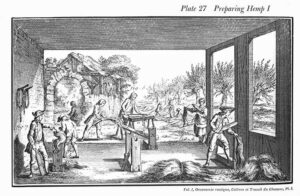

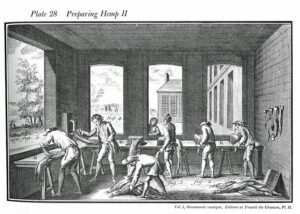

Illustration

18th century France

Hemp and flax were processed in similar ways. Note at left the workers rotting flax in a stream (fig. 1), drying flax (fig. 3), using the flax break (fig. 5), and using the scutching knife (fig. 7). At right, see the use of the hatchel (fig. 1-3).

From the Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry

Pictured here roughly from left to right:

Hatchel

1828

Looking like a deadly weapon, this hatchel belonged to Anna Zeigler and is marked AOZ 1828.

Gift of Laura Zeigler

Hatchel with Cover

1771

Wooden covers no doubt decreased the probability of injury when hatchels were not in use.

Gift of C. R. Coburn

Scutching Knife

Resembling a long paddle, this scutching knife was used to remove hard pieces of outer stalk from the flax plant and smooth and scrape the fibers clean. The flax is held on a board and beat with this knife, as can be seen in the illustration.

Gift of S. Washington Lehn

1905.011.001

Strick

Hatchelled flax ready to be spun can be seen here in the photo. The amount of flax considered to be one strick was not weighed, rather it was determined by a comfortable handful for the hatcheller.

Gift of Dr. Charles B. Fager

Cards

Made in Philadelphia, PA

Possibly used on the John Loose farm in North Middleton Township.

This tool, pictured here far right in the exhibit case, resembles today’s pet brush. The small teeth align the fibers of wool, tow, or cotton so they can be twisted into yarn.

Gift of Barbara Egolf

Fibers

Flax Seed to Linen Fabric

To learn more about spinning flax and turning flax into linen, watch How to make Linen from Flax from Mount Vernon:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Eec859dAhg

Shorn Wool to Yarn

If you would like to learn how to turn shorn wool into yarn go to the Crafty Katie website:

https://craftykatiegates.wordpress.com/2012/08/01/processing-raw-fleece/

From Fiber to Fashion – The Weaver

The Weaver

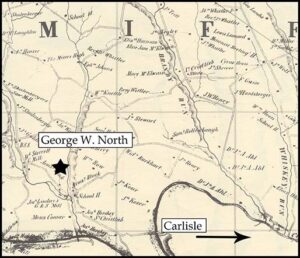

George Washington North

George Washington North (1792-1835) began work as a weaver, but later purchased some land and became a farmer. As a weaver in Mifflin Township, George produced fabric for an average of twenty neighboring households. Most people did not do their own weaving, since looms were a large, expensive piece of equipment. Looms were owned by about 12% of Cumberland County’s population from 1750 to 1800. George typically received payment for taking in his client’s spun yarn and returning it in the form of fabric. He also bought yarn in order to make his own cloth to sell. The coverlet hanging in this gallery exhibition photo was woven by George North.

Looms

Loom

1775-1800

Oak

Collection of Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum

Cloth

Linen

Produced at the Gutshall farm in North Middleton Township.

Gift of Mary Lefkowski

Carpet Loom Photo

1911

Carlisle Carpet Mills

Over 100 years later, a similar loom is being used to weave carpets. The weaver sits on a bench built into the loom. He uses foot pedals to raise and lower the heddles, which hold the warp threads of the fabric. Next to him on the bench is the shuttle. He passes the shuttle back and forth to add the weft threads to make the cloth. The beater that he has his hand on is pushed against the weaving to keep it tight and even. The finished fabric wraps around under the loom.

Tape

Colorful tapes were woven for decorative purposes, like garters or apron ties. Plain tape was more utilitarian and found, for example, on ties for grain bags.

Collection of Charles and Tandy Hersh

CCHS Volunteer Eileen Miller demonstrates weaving with a reproduction tape loom at the Cloth & Costume exhibit opening.

Type of Fabric

Coverlet

1800-1825

George Washington North

Mifflin Township

Woven by George North, this is a single coverlet with a turned twill or double-faced twill weave. The two halves of the coverlet were woven the width of the loom, then sewn together to make the finished size.

Gift of Mrs. E. Filbert Stuart

Towel

1800-1825

George Washington North

Mifflin Township

When George died in 1835, he was survived by his widow and three children. His son George and unmarried daughter Mary were both tailors. The two siblings moved to Newville, where they lived along with their widowed mother, Rebecca. Woven by George North, Mary is said to be the one who embroidered this hand towel.

Gift of Mrs. E. Filbert Stuart

Finishing

After weaving, wool fabric could be fulled. A fulling mill beat wet cloth, cleaning it as well as shrinking and melding the fibers together in a felt-like manner. In Cumberland County, professional fullers operate mills as early as 1759.

Spinners also mixed fibers to create cloth with different properties. Linsey-woolsey, for example, combined the warmth of wool with the durability of linen.

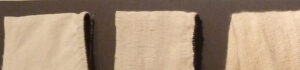

Pictured in the photo from left to right

Unfulled linsey-woolsey cloth, just off the loom (left). The same cloth after being fulled (middle) and another version of this cloth.

Bed Linens

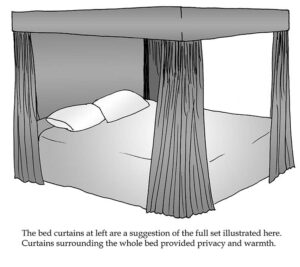

The Bed

In the 1700s, the term “bed “did not include a wooden frame. Instead, it meant a stuffed bag for sleeping on, also called a tick. The tick could contain straw or feathers and was placed on the floor or on a bed frame. The tightly-woven cloth made to contain the stuffing was called ticking because of this use. A stuffed tick could contain 50 or 60 pounds of feathers.

The sheets and pillows used on a bed were called bed furniture. Since a finished sheet was wider than most looms could weave, bed coverings were sewn together and finished by hand. The poorer residents might have slept on the floor with a tick and a blanket or two, while a wealthier family could afford a wooden bed frame and possibly even bed curtains.

Bed Coverings

County inventories show that many beds were covered only with blankets. Blanket-quality cloth was produced locally, but manufactured blankets were available from Philadelphia and were a popular trade item with Native Americans in this area. Bed rugs, a large piece of fabric resembling a hooked rug, were another bed covering used in the 1700s.

First seen in the records of wealthy households, quilts and coverlets grew more common from the late 1700s on. Sixty percent of households owned at least one quilt in this period. At first, whole cloth quilts like the one on this bed were popular, with stitching as the decorative element. Pieced quilts created from a variety of fabrics were being made by 1800. Weavers produced coverlets in more colors and a greater variety of patterns than bed rugs and whole cloth quilts.

Pictured here:

Bed Frame with Trundle Bed

19th century

Soft wood

Originally painted red, this rope bed was used by the James Coyle family of South Middleton Township.

Gift of Mary Lefkowski

Bed Tick

Linen

As mentioned above, the bed tick functioned like our present-day bed mattress but was more like a large bag filled with straw or feathers, depending on what the owner had available or could afford.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Sheet

Linen

People commonly used only one sheet on their bed.

Gift of Edna Holtzman

Quilt

Wool

Whole cloth quilt. Unlike its later colorful, small-pieced counterpart, early quilts were made in one color and of large woven fabric sewn together. The makers of these early quilts added decorative elements through stitching.

Collection of Terry Drachbar

Bolster

Linen

Fabric for bolsters, pillows, and bed ticks had to be woven very tightly in order to hold feathers or straw.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Pillowcase

Linen

Decorated with handmade lace and embroidered in silk with the owner’s initials, “P.O.” this case was made to cover a pillow.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Blanket

1775-1800

Belonging Martha Ramsey Means (1752-1849), this item was handed down to her descendants who settled in Cumberland County. Family history states, “She was a brave, self-reliant, God-fearing woman, and several years after her husband’s death removed from Dauphin County to Allegheny County, carrying on the backs of pack animals her household effects and her children, one of whom was a baby boy who was not yet born when his father died.”

Gift of Mrs. James D. Flower

From Fashion to Fiber – The Tailor

The Tailor

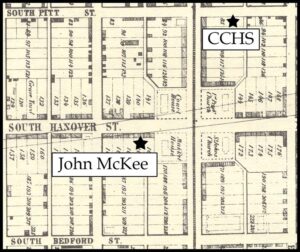

John McKee

Clothing was created by professional tailors, seamstresses, mantua [gown] makers, and by householders. John McKee and his brother Andrew were tailors in the 1760s and 1770s in Carlisle. John’s profits paid his debt to the Carlisle storekeeper where he and his wife purchased brown sugar, salt, and other necessities. John also purchased items at this store needed for his trade, such as thread and cloth. As a tailor, John constructed garments for a living, however he also made repairs and alterations on clothing that could not be done by the average person. Clothes were an investment, even handed down in wills, so it was important to make an effort to protect and extend the life of a garment.

Our tailor in this exhibit is wearing the items listed below. Included in this listing is the child’s shirt being altered.

Shirt

18th century

American

Linen

Handmade thread buttons and needle-lace reinforcement at neck. The cuffs are protected from wear by little knots called mice teeth. They are designed to be replaced when worn down.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Waistcoat

Mid 1700s

American

Piqué weave

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Reproduction Breeches

Child’s Shirt

19th century

American

Linen

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

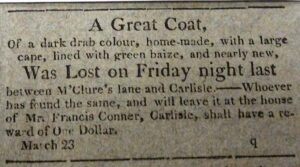

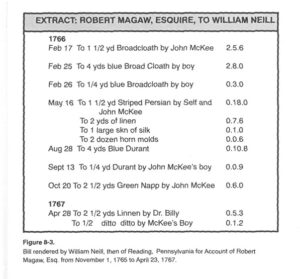

Extract of Bill

One of John McKee’s regular clients is his next-door neighbor, Colonel Robert Magaw. John often purchased cloth for his clothing on Magaw’s store account. In one instance, the two men together picked out some striped Persian, a fine silk perhaps used to make a waistcoat or the front of a jacket. They also purchased linen which could have been used for the lining. The large skein of silk (versus a small skein) may have been used for embroidered embellishment on the same garment. The bill shows that John billed Magaw directly for his labor and the cost of the additional supplies, such as thread and buttons. The horn button molds were simple forms that were meant to be covered in fabric for use with the jacket or breeches.

Bill published in Cloth & Costume from Collection of the CCHS Library Archives.

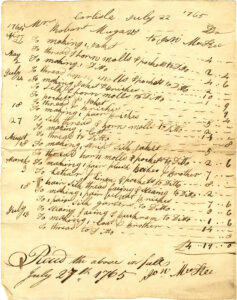

Bill

Carlisle, July 22, 1765

John McKee billed Robert Magaw for work done between April 26, 1764 and July 13, 1765.

Collection of the Pennsylvania Historical Society

Like all tailors, Carlisle tailor John McKee sat cross-legged on a table to keep his products clean and off the floor. Here, re-enactor and CCHS volunteer Tad Miller demonstrates his tailoring skills during the Fiber to Fashion exhibit opening.

Tailor’s Tools

back half of case, seven items

Buttonholers and Tailor’s Hammer

The hammer was used to tap the buttonholer chisels through layers of fabric. The cutter below would have been rocked back and forth by hand.

Collection of Kenelm Winslow

front row, far right

Needle Case

Gift of Jane Smead

front row, second from right

Hand-forged Shears

From the Ege Mansion in Boiling Springs.

Gift of Vilma Bucher

Clothing

Getting Dressed

The first item of clothing a person put on provided a hygienic layer between the skin and outer clothing. For men, this item of clothing was a shirt and for women, a shift. These garments were typically made of linen and their length extended below the knees to provide extra protection in an era before drawers or underpants.

Shift

1775-1800, American

Linen

The shift (pictured here hanging on the wall behind the case) provided a hygienic layer between the skin and the clothing worn over it. The shift was worn underneath the stays. The length extended below the knees. The scoop neck and form fitting sleeves were designed to fit snugly under a dress.

Collection of Mary Doering

Stays

1760-75, American

Wool and linen

In the eighteenth century, women’s corsets were known as stays, and they created the basic shape for the clothing worn over it. The stiff shape of the stays was formed by narrow bands of boning, usually whale baleen or cartilage. These stays are notable for the extensive figure reinforcement created by narrowly spaced vertical channels of baleen, as well as the horizontal bands of wood placed at the center front of the abdomen. In addition, a busk was inserted in a blue and white linen pocket down the inside of the center front. The two shades of wool used on the exterior suggest that the stays were enlarged. Stays were normally worn with a gap of several inches at the center back, so the original owner probably had a waist measurement of approximately 30 inches.

Collection of Mary Doering

Busk

1770, New England

Wood and ivory

Eighteenth century busks (hard to see here, lying inside the case in front of the stays) were usually made from wood with one side carved with decorative designs. When worn, they depressed the diaphragm and reinforced the elongated conical shape of the stays.

Collection of Mary Doering

Coat

1800–1820

Silk

Belonged to John Brown.

Gift of Sarah and Emeline Parker in memory of John Brown Parker

Waistcoat c.1780

Silk

Belonged to John Brown (1748-1833), who was born in Ireland and lived most of his life in Philadelphia. He was involved in the political affairs of the country and counted among his personal friends George Washington, John Paul Jones, and Benjamin Rush. He served as Secretary of the Pennsylvania State Board of War and Secretary of the Marine Committee and Board of Admiralty.

Gift of Sarah and Emeline Parker in memory of John Brown Parker

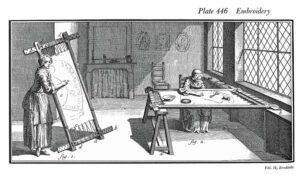

Embroidery of a similar waistcoat in 18th century France. Vests of this type were commonly embroidered first on flat cloth. Then, the purchased cloth was cut to size and sewn together by a tailor.

From the Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry

Embroidery

Since embroidery could be done at home by women, it was considered less expensive than paying a professional dyer to create patterns in cloth. Embroidery was a skill important for young girls to learn, if only for the practical reason of marking family linens. This way, families who could afford to send linens out to be washed could be confident that the correct pieces would come back. Carlisle was home to several embroidery teachers during the eighteenth century.

Gentleman’s Suit c.1780

English

Silk waistcoat, coat and breeches

Although the coat and breeches of this suit were not originally worn together, their complementary color and woven pattern suggest they could have been compatible. Gentlemen traditionally wore knee length breeches that were fastened by buckles over the stockings underneath. While the legs of the breeches were form fitting, a voluminous gathering of fabric at the center back allowed men to be seated comfortably inside a home or astride a horse.

Waistcoats were often the most decorative component of a man’s suit and they frequently featured lavish floral designs. Tambour embroidered roses decorate the front of this waistcoat, in contrast to the more humble linen used for the back. Normally only the front of a waistcoat was visible and expensive silk fabric was not wasted where it was not visible.

The suit is shown with a reproduction linen shirt dickey, stock, cuff ruffles, and reproduction shoes.

Collection of Mary Doering

Young Woman’s Gown c.1790

Silk jacket and petticoat

Fine wear for women could be made from taffeta, fine wool, damask, chintz, or calico prints, but was not limited to these choices. The pierrot was a close fitting, low necked jacket with tails that was popular in the 1780s and 90s. It was designed to be fastened with pins.

Collection of Becky Manifold

Child’s Banyan or Wrapping Gown

Linen

Pictured here hanging on the wall, this garment would be tied with a sash when worn. A banyan was an informal men’s garment worn at home. Its design was inspired by Asian textiles.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Dress

1820 – 1830

Printed Cotton

Collection of Becky Manifold

Boy’s Suit

1800-1830

Collection of Becky Manifold

Pocket, Pocketbook, or Wallet?

Terms still in use today have changed from their 18th century meanings. The large, white item pictured here in the back of the exhibit case is a wallet, and was meant to be filled at both ends and slung over the carrier’s shoulder or over a horse to transport goods. It is the equivalent of today’s backpack. Today, of course, a wallet is a small item where a person carries money and important documents. However, items used for this purpose in the 18th century were called pocketbooks, whether carried by a man or a woman. The 18th century pocket is similar to what we call a pocket today, although only men had clothing with built-in pockets. For women, the pocket was a separate item tied around the waist and accessed through slits in the gown or petticoat.

back of case

Market Wallet

Bleached linen

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

front row, second from left

Sermon Carrier

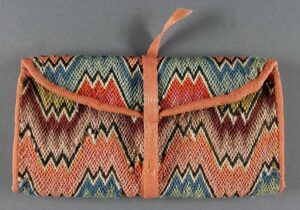

1767

Wool on linen ground

Belonged to Reverend Conrad Bucher, first minister of the Reformed Church in Carlisle. Used to carry his bible, notes, and other records that he might need as a traveling preacher in Ohio and Maryland.

Collection of the First United Church of Christ, Carlisle, Pennsylvania

front row, far left

Pocketbook

1778

Silver latch is marked with the date and “G.S.” for the owner’s initials. Dr. George Stevenson was a lieutenant in the Revolutionary War and later a surgeon. His invitation to dinner with President George Washington rests inside.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert Keller

front row, far right

Pocket

Dimity

Pockets were not built into women’s gowns. This was tied around the waist and worn under her petticoat.

Collection of Becky Manifold

Examples of mid to late 18th century pocketbook (top) and an embroidered woman’s pocket (bottom). For more examples of pockets, pocketbooks, and wallets, go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art website and search their Online Collection Database.

man’s embroidered pocket:

https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/127634.html

https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/139831.html?mulR=978932862%7C4

woman’s embroidered pocket:

https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/139831.html?mulR=978932862|4

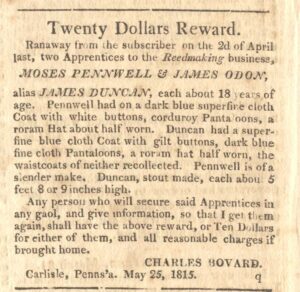

Identity

The quality and expense of the material used in a garment indicated the owner’s profession or position in society. Clothes were a valuable investment, and people often were described in terms of their clothing. Advertisements for the capture of escaped enslaved persons and runaway apprentices included a very detailed description of their clothing. Clothing for enslaved persons was typically provided by their owner, while indentured servants received two sets of clothing: one for daily wear and one new set upon completion of their apprenticeship.

Although a small percentage of inventories show that Cumberland County residents owned Native American clothing, most colonists preferred to wear clothes familiar to their own ethnic background. Styles from London and Philadelphia were widely advertised and imitated in the county. Colonial culture occasionally demanded people change hunting shirts and moccasins for court silks. Such was the case for George Croghan, an early trader well known on the frontier, who donned white worsted breeches, silk stockings, and a velvet dress suit for his 1764 visit to London.

Just like today, the clothing a person wore during the colonial period indicated a person’s occupation or status in society. Pictured here are CCHS Staff Rob Schwartz, Rachael Zuch, and Cara Curtis in reproduction clothing for the Cloth & Costume exhibit opening in 2011.

From Fiber to Fashion – The Storekeeper

The Storekeeper

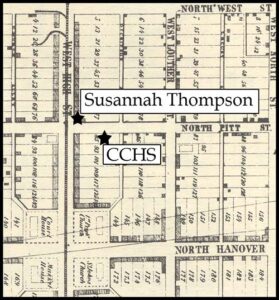

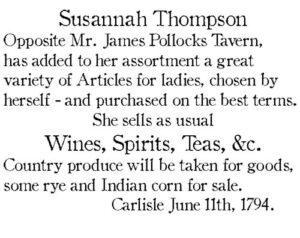

Susanna Ross Thomson

Susanna Ross Thomson (1731-1801), a native of Delaware, came to Carlisle in the mid-1700s where her husband, Reverend William Thomson, served as the rector at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Carlisle. Known as a cheerful, social woman, she began her general store in the 1790s after her husband died. Although she owned the store jointly with her son-in-law, James Hamilton, it was Susanna who went to Philadelphia to buy fashionable goods, imported fabrics, and jewelry. She also dealt in household goods and food, buying and selling locally made items. Susanna’s store opened after the Revolutionary War, so she did not suffer a loss of business when imports were no longer available. With an initial investment of 637 pounds, Susanna and James split a gross profit of 120 pounds in their first year.

Credit

Credit was very important at Susanna’s store, like most others in early Cumberland County. Susanna bought her first load of goods on credit, sending wagon loads of flour later to pay for her wares. Customers would settle their credit account either by payment in cash or in goods. For example, Susanna accepted payments of cloth in all stages, whether spun yarn, woven linen, or tailor work.

Ledger

August 1792- June 1795

Pictured here in the exhibit is Susanna Thompson’s account book. Her customers on this page include Carlisle residents Doctor Gustine, clockmaker Jacob Herwick, her son-in-law James Hamilton, and her sister, Catherine Thompson.

CCHS Archives

Scales

For coins or weighing products.

Gift of Eleanor L. Bowman

Copper Coins

Draped Bust, Connecticut, 1787

Liberty Head, 1794

Gift of Samuel Wilhour

Thirty Shilling Note

1775

Printed by Hall and Sellers, Philadelphia, PA

This paper contains sparkling flakes of mica.

One Penny Note

1789

Printed by Kline and Reynolds, Carlisle, PA

Gift of the Dauphin County Historical Society

Our storekeeper in this exhibit is wearing the items listed below.

Shortgown

18th Century

Stamped cotton

The short gown was popular for everyday wear. Less affluent or working women might wear a linsey-woolsey gown or a cotton short gown with a contrasting petticoat.

Collection of York County Heritage Trust

Kerchief

c. 1820

Collection of the Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Cap

c. 1810

Embellished with Hollie point embroidery.

Collection of the Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Petticoat

c. 1800

Wool

What we would call a skirt today was known as a petticoat during the eighteenth century, whether it was an inner or outer garment. Some gowns were cut away in the front in a style that would reveal the decorative petticoat underneath.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Store Goods

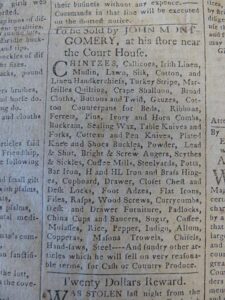

Examples of Stores

Examples of the inventory you would find in a local stores during this period.

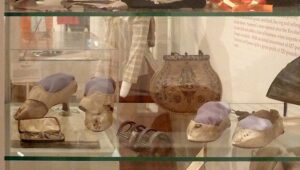

Exhibit Store

Bonnet Shelf at Exhibit

Left to right

Quaker Cap

1800-1830

Silk

Collection of Rebecca Manifold

Baby Cap

Embellished with Hollie point embroidery.

Collection of the Shippensburg University Fashion Archives

Shoe Shelf at Exhibit

Shoes

Like most other items, shoes could be made in America or imported. Local cobblers, called cordwainers, got leather from local tanners to make men’s shoes and boots. Women’s shoes were usually made of more delicate leather, or fine fabrics like silk or worsted. At this time in shoemaking history, cobblers did not differentiate between shoes made for the right or the left foot. Instead, shoes were made on a straight last and shaped by the wearer’s use.

back row, left to right

Slippers

1770-1780

Silk

Made by Job Heath

Collection of Rebecca Manifold

Purse

1800-1820

Paper and silk with steel spangles

Collection of Rebecca Manifold

front row, second from the left to right

Men’s Shoe Buckles

1780-1790

Collection of Rebecca Manifold

Shoes

Women’s white leather c. 1790

Originally decorated with spangles and silver metallic thread.

Gift of Charles Frederick Showers

Cloth

Locally Woven

Whether locally made or imported, early Cumberland County people had access to approximately 138 different types of cloth. This total does not include the different colors or patterns available. Local weavers produced plain linen of several grades, including checked and striped patterns. Linen was the most common fabric used in the home. It was found in clothes, bedding, and tablecloths, with coarser linen used for covers and bags. Local wool products were called worsted, blanketing, coating, camlet, and thick cloth.

Imported

Cloth was one of the major imports of the American colonies and fabrics of complicated weave or coloring were likely imported. Fabrics from Russia, Germany, India, and China passed through English ports on their way to America. Wool and linen were two of the most imported types of cloth, although special fabrics such as silks, velvets, and cottons were also typically imported. Imports sharply dropped from 1776-1783, when the Revolutionary War cut off trade with Britain. However, trade resumed rapidly after the war’s end.

back row, left to right

Resist-dyed Linen

Probably made in the late 1700s or early 1800s, the textile pictured here in the back of the exhibit case is a stamped or resist dyed fabric that could be used for bed curtains or for clothing.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Textile Printing Block

Sour gum wood

Precision was required to accurately repeat a pattern over a length of cloth.

Collection of Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum

front row, left to right

Dye Book

1847

This book of formulas belonged to Carlisle weaver Henry Harkness.

CCHS Archive

Cotton Yarn

Cloth could be dyed after it was woven with undyed yarn or cloth could be woven with dyed yarn. One of the skeins exhibited here is natural, undyed yarn, while the other skein has been dyed yellow.

Indigo

Both of the resist-dyed textiles have been dyed blue with indigo.

Resist-Dyed Fabric

Flax for John Loose’s textiles was grown, spun, and perhaps woven on his farm at Waggoner’s Gap Road. The resist-dying was said to have been done by a blue dying business in Carlisle.

Gift of Barbara Egolf

Locally Woven

Whether locally made or imported, early Cumberland County people had access to approximately 138 different types of cloth. This total does not include the different colors or patterns available. Local weavers produced plain linen of several grades, including checked and striped patterns. Linen was the most common fabric used in the home. It was found in clothes, bedding, and tablecloths, with coarser linen used for covers and bags. Local wool products were called worsted, blanketing, coating, camlet, and thick cloth.

Imported

Cloth was one of the major imports of the American colonies and fabrics of complicated weave or coloring were likely imported. Fabrics from Russia, Germany, India, and China passed through English ports on their way to America. Wool and linen were two of the most imported types of cloth, although special fabrics such as silks, velvets, and cottons were also typically imported. Imports sharply dropped from 1776-1783, when the Revolutionary War cut off trade with Britain. However, trade resumed rapidly after the war’s end.

back row, left to right

Resist-dyed Linen

Probably made in the late 1700s or early 1800s, the textile pictured here in the back of the exhibit case is a stamped or resist dyed fabric that could be used for bed curtains or for clothing.

Collection of Tandy and Charles Hersh

Textile Printing Block

Sour gum wood

Precision was required to accurately repeat a pattern over a length of cloth.

Collection of Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum

front row, left to right

Dye Book

1847

This book of formulas belonged to Carlisle weaver Henry Harkness.

CCHS Archive

Cotton Yarn

Cloth could be dyed after it was woven with undyed yarn or cloth could be woven with dyed yarn. One of the skeins exhibited here is natural, undyed yarn, while the other skein has been dyed yellow.

Indigo

Both of the resist-dyed textiles have been dyed blue with indigo.

Resist-Dyed Fabric

Flax for John Loose’s textiles was grown, spun, and perhaps woven on his farm at Waggoner’s Gap Road. The resist-dying was said to have been done by a blue dying business in Carlisle.

Gift of Barbara Egolf

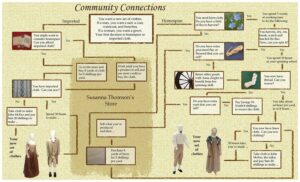

Community Connections

How would you have dressed in the 18th century? Look at the flowchart above and imagine living the life of a farmer, tailor, storekeeper, lawyer, or anyone you choose. Ready? Now start at the top and see where your path leads you. Click here for a larger version.

Many choices were simplified to make this chart. Estimates of time and cost are broad averages because these factors varied widely based on type of material and the product being made. For example, a man’s suit took more cloth and work, making it more expensive than a woman’s gown.

If you would like to learn more about early Pennsylvania clothing and textiles you can order the book we used for this exhibit Cloth and Costume, 1750 to 1800 here.

From Fiber to Fashion – Thank You

A Special Thank You

to

Tandy and Charles Hersh

For their book Cloth and Costume 1750-1800 which inspired this exhibit, and for the generous gift of their time and expertise.

Special thanks to all who helped create this exhibit

Dr. Karin Bohleke, Major Tad Miller,

CCHS Museum Committee, Volunteers, and Staff

And exhibit opening demonstrators

Maj. Tad Miller & Capt. Eileen Miller

Our thanks to the following contributors

Mary Doering

Terry Drachbar

First United Church of Christ, Carlisle, PA

Tandy and Charles Hersh